During his 10 months in jail the jockey and drover drew 82 drawings of life on the outside, while controversy raged over his sentence. Charlie Flannigan, an Aboriginal stockman, showed “unalterable coolness” as he was taken to the gallows, newspapers at the time reported. It was 1893 and the convicted murderer was about to become the first man hanged in the Northern Territory. Flannigan’s execution sparked controversy, as a white man found guilty of murder at the same time had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

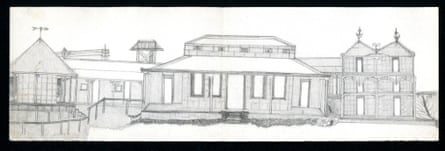

More than a century later a Muran man, Don Nawurlany Christophersen, has pulled together Flannigan’s story as told in newspapers and records of the time, in a new book called A Little Bit of Justice. After Flannigan was found guilty of murdering a white man, he spent 10 months on death row sketching moments of his life. He created 82 artworks in his dank, tiny cell at the Fannie Bay gaol using paper given to him by the guards. Flannigan’s drawings will appear in an exhibition of the same name as the book which opens on Saturday at the South Australian Museum.

‘I shot him in the chest’

Before the murder, Flannigan, a prize-winning jockey and drover, went to the Auvergne cattle station in the NT looking for work. One night he was playing cards – cribbage – with the station’s manager, Samuel Croker, a station hand called Jock McPhee and Joe Ah Wah, the Chinese cook. “All hands were playing cards for sticks of tobacco,” the Northern Territory Times & Gazette wrote. According to some reports, Croker threatened Flannigan first then went for his revolver. Flannigan grabbed a rifle and shot Croker. McPhee reported that Flannigan said: “That old bastard has done me a lot of harm.”

The men dug a grave, Flannigan sewed the body up in a blanket, they made a coffin out of galvanised iron, and Flannigan was reported by some to have said: “Well, old fellow, I’ve had the pleasure of sewing you up instead of you sewing me up.” And then: “You old bastard, you are better there than a young fellow like me.” Flannigan at first went bush then later handed himself into police. He said Croker had acted threateningly with his gun and that during the card game Croker called him a “thick-headed bastard”, and threatened to “brain” him, so Flannigan got his rifle. “He was sideways on and I shot him in the chest and he fell down,” he said. It was also reported that Croker was involved in the frontier killings of First Nations people.

Flannigan pleaded not guilty but the jury returned a “unanimous verdict of guilty of wilful murder”, the newspaper reported.

‘There should not be a colour test in crime’

Meanwhile, George Page, a white man, had also been sentenced to death after he killed his niece (for whom he had a “guilty passion”) in a jealous rage. But unlike Flannigan, he had his sentence commuted to life with hard labour. Fury erupted, with a delegation of citizens petitioning the South Australian government – which at that stage oversaw the NT – for equal treatment of the men. “They did not ask that the sword of justice should be sheathed, but that its stroke should be felt equally by whites and by blacks,” the newspaper reported. “Its only petition was that there should not be a colour test in crime.”

Another paper, the Register, reported that “the public conscience has never before been so deeply stirred by a keen sense of injustice”. “The contrast between Page and Flannigan is most impressive … Page has a white skin. Flannigan has not. “We are sorely afraid that that is generally regarded as the reason why he, though the less morally guilty of the two, is to die while Page is to live.” But the petition didn’t work.

In his 9 foot by 9 foot cell, awaiting his death, Flannigan was shackled and chained to a ring on the wall at night, and had a bucket for a toilet.

There, he drew homesteads and stations, horses and stockmen, self-portraits and campsites. He drew the things that made up his life. The sketches ended up in the SA Museum archives until they were discovered 130 years later by Christophersen, a historian and curator. “[Flannigan] got better and better in the 10 months he was in gaol,” Christophersen says. “You can imagine him sitting, shackled in his small cell, with nothing to look at other than what’s in his head – and he recreates those images in paper.”

A final goodbye

Christophersen says he wanted to do Flannigan’s story justice, to tell it “the right way”. “It’s his life that he’s chronicling, where he’s worked, what he did, right up to the last image of Fannie Bay gaol,” he says. That picture of the gaol is in Flannigan’s trademark neat lines, with “long fellow waves tay tay” written above it. “I take the ‘long fellow’ to mean his neck being stretched on the gallows and the ‘waves ta tay’ is his saying goodbye,” Christophersen writes.

The NT Times and Gazette reported on 21 July 1893 that gallows had been erected in the prison yard. The prisoner had his last breakfast, a last smoke. “He never once betrayed a sign that he was going to his death,” the newspaper reported. As he walked out he did so “with the firm step of a man going to freedom rather than of one about to be killed”. “Up the steps to the platform he ascended with the same unalterable coolness, and placing himself on the trapdoor, he stood erect and for a second or two surveyed the yard and those in front of him while the hangman bound his legs with rope.” The noose was adjusted, a black cap pulled over his face. Flannigan said he was “was sorry for the life he had led, but hoped it would be all right where he was going”. “Then the signal was given, the bolt was drawn… and the spirit of the murderer flashed into eternity.” Death was “instantaneous”, the newspaper reported.

Source: Tory Shepherd The Guardian Australia